World Wicker and Weaving Festival 2023 in Poland Part 4: The Swedish Exhibition 世界かご編み大会2023 in ポーランド 4 -スウェーデンの展示-

The indoor venue was divided into two main areas.

One area was dedicated to live demonstrations by the competition participants.

The other consisted of booths where works could be exhibited and sold.

Here, we would like to introduce the exhibitions from each country.

We begin with the display from Sweden.

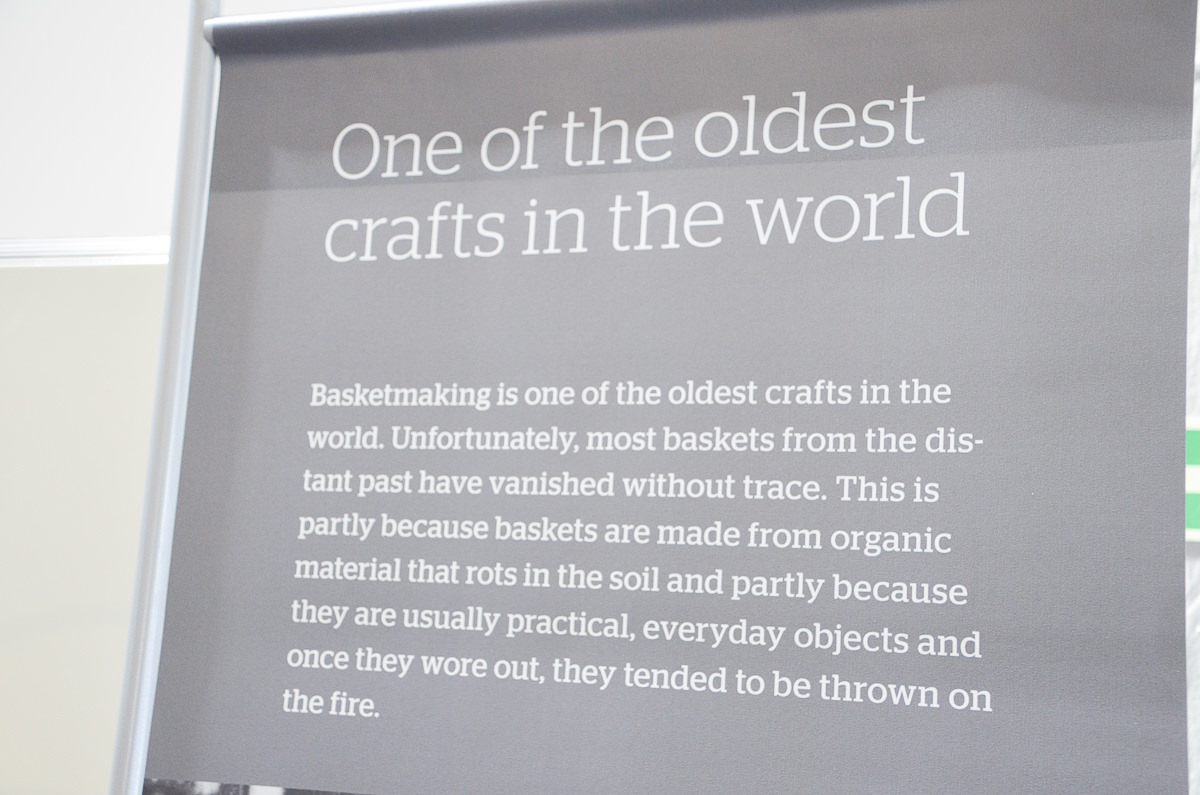

The exhibition explains that basketry is one of the oldest forms of handcraft in the world. At the same time, it also conveys the unfortunate reality that many of these techniques are no longer being passed down, and that some have already been lost.

Some of the reasons given include the fact that baskets were made from materials that decompose in the soil, and that for people they were ordinary, practical objects. Once they had been used, they were often simply burned.

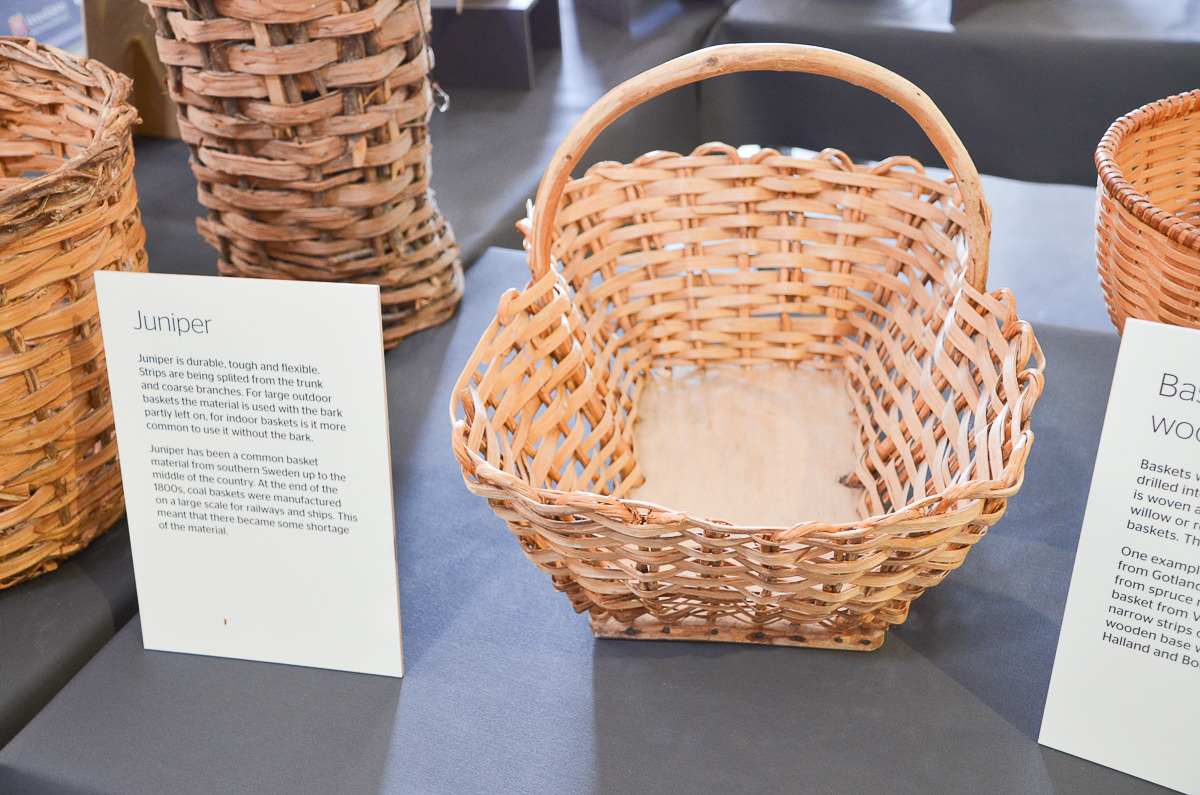

This basket is made from a material known as juniper. Juniper is a tree of the cypress family (Juniperus), also called Western juniper,

and its berries are an essential element in the characteristic aroma of gin.

This is a double-handled basket, also made from juniper. With its rugged and powerful construction, it was traditionally used for tasks such as gardening, fishing, and carrying coal for use on the railway.

This basket is made from goat willow and appears to have been produced in central Sweden. The same material was also traditionally used in basket making in northern Japan, where goat willow was combined with other local plant fibers. It is striking to see this shared choice of materials across cold regions in different parts of the world. Unfortunately, it is said that the techniques used to make these baskets are no longer being passed down, and that there are no makers who can produce them today.

In southern Sweden, it appears that baskets were woven using willow, much like in other European countries.

There were also baskets made from hazel, the tree that produces hazelnuts. Baskets woven from hazel can also be found in Poland.

There were also baskets made from pine and birch, materials commonly seen in nearby regions such as Estonia.

We had the opportunity to speak at length with the Swedish participants

who presented this exhibition, and to exchange a great deal of information.

For example:

• Sweden, like Japan, is a country that stretches far from north to south.

Because the climate varies by region, several different materials

have traditionally been used for basket making.

• In the past, there were remarkably many types of baskets,

each designed for a specific purpose.

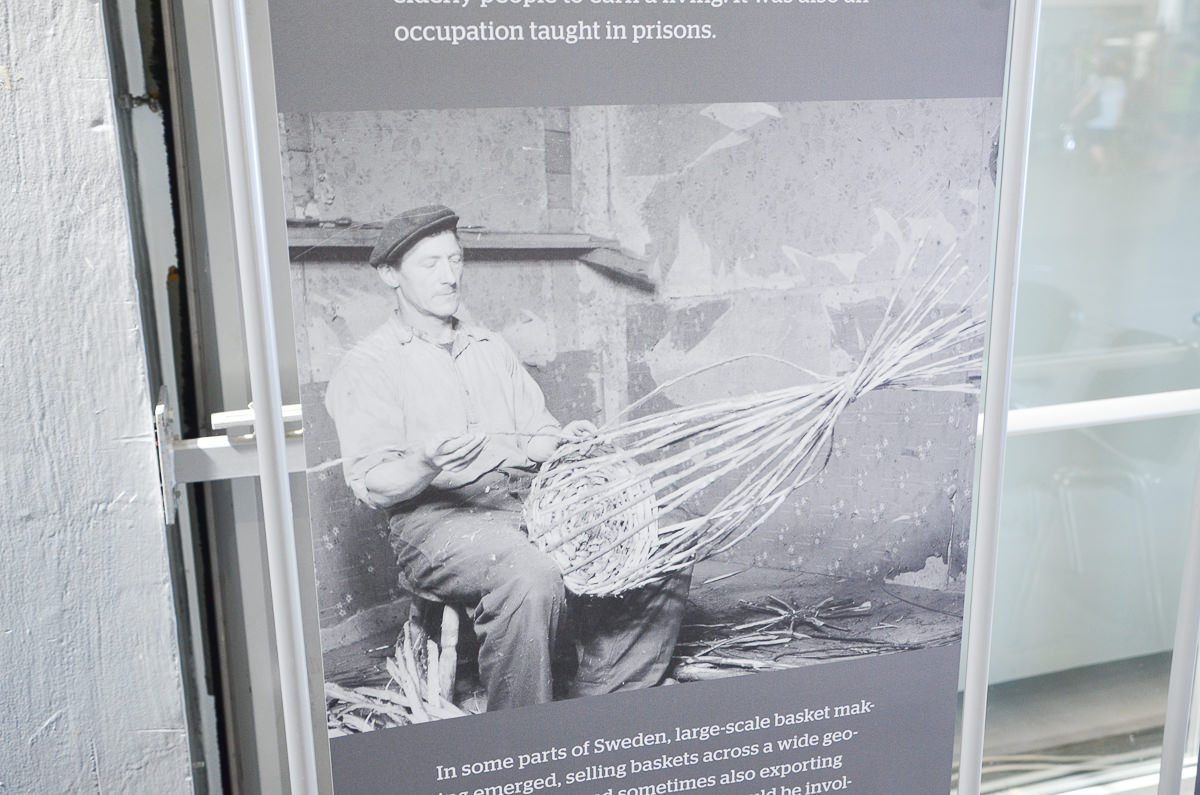

• Basket making was originally regarded as work associated with

lower-income communities, and it was also taught as a vocational skill

within prisons.

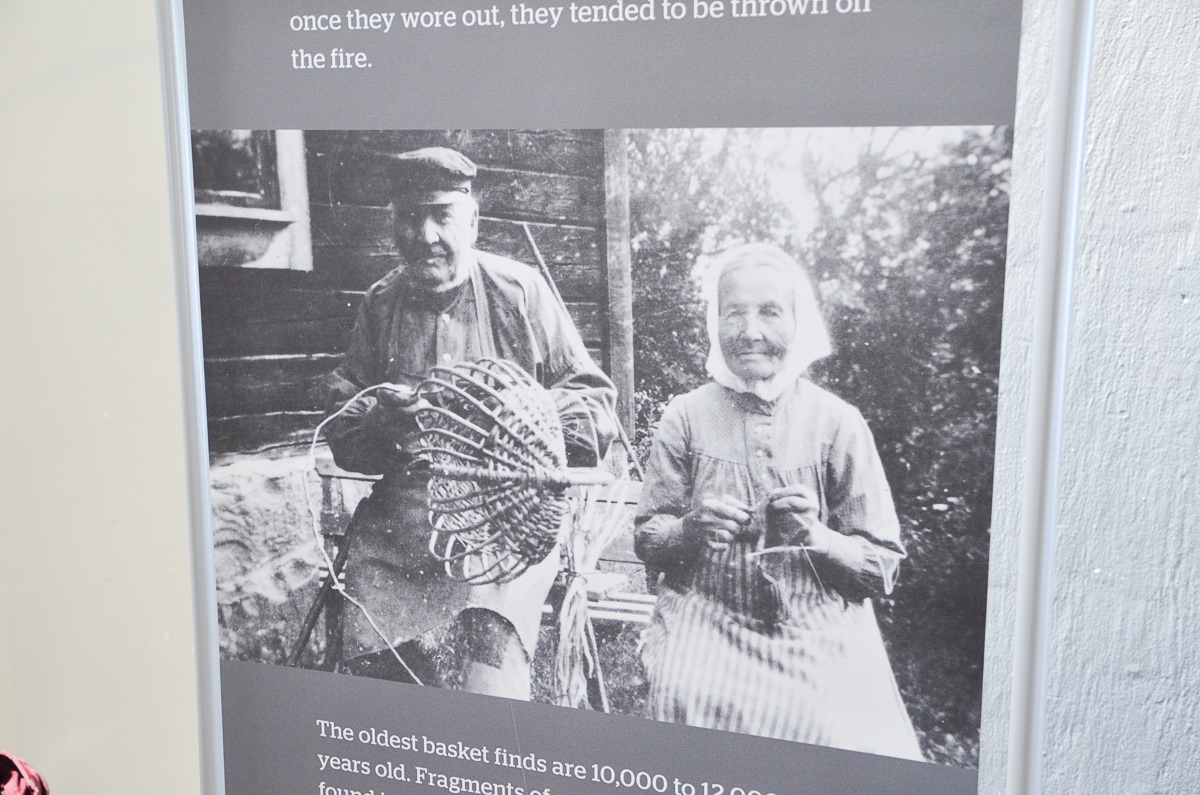

• From the 19th century through the early 20th century,

basket making became an important source of cash income

for small-scale farmers, elderly people, and people with disabilities.

• In some regions and villages, basket making grew so widespread

that nearly everyone was involved, and baskets were even produced

for export abroad.

• As basket making came to be recognized as an industry,

the social standing of basket makers improved.

This, in turn, helped foster movements to protect traditional handcrafts,

and baskets gradually began to be sold through craft shops

within the country.

Through this exhibition, we were able to reaffirm that the history

traced by Japanese baskets, sieves, and winnowing trays,

and the traditions found in Sweden—despite the great geographical distance—

are not so far apart in their lineage.

We hope to stay in touch with these Swedish makers,

so that we may one day introduce Swedish basketry

to everyone here as well.

Tomotake Ichikawa

+++++++++++++++++++

To be continued